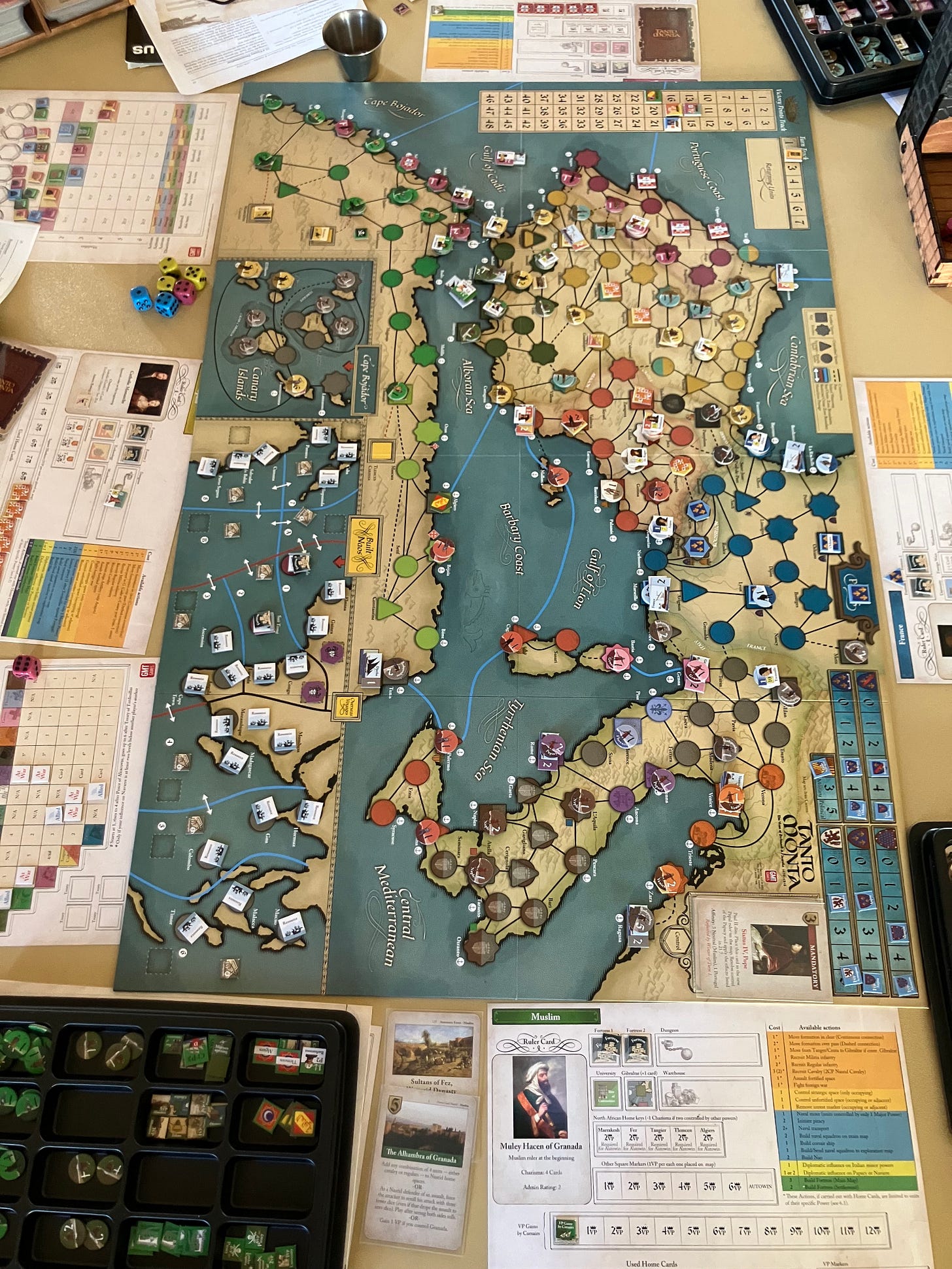

When I say that I hung out with a bunch of middle-aged wargamers burying their noses in rules booklets at ConQuest Ventura couple of weeks ago, I was, at most, half-joking. I spent all day Saturday with a couple of friends working through a few turns of Tanto Monta: The Rise of Ferdinand and Isabella, the recent GMT Games offering that uses an adaptation of Ed Beach’s Here I Stand/Virgin Queen system to take a wide angle view of the Reconquista. As such, it’s a strategic-level, point-to-point movement game that encompasses not just Aragon, Castille and Granada, but also the effect that the rise of a unified Spain had on Portugal, France, the Ottomans and Muslim North Africa. I don’t want to treat this as a proper review because I had little prior knowledge of the game; I learned of it what I could from having it explained to me as I went along; and we only played through a few turns before my companions decided that they had met their objective of figuring out how it works.

In other words, I feel like I didn’t put enough effort into the game to properly review it. Instead, I’ll just use it to illustrate one of my pet peeves about historical wargames and move on.

First of all, I’d like to make it clear that I came to appreciate Tanto Monta as we made our way through it. There aren’t many games on the Reconquista, so kudos to Carlos Diaz Narvaez for designing one. As we became more comfortable with the rules, we could see the sense in a lot of his design choices and the game really does shed some light on the rise of Aragon and Castille in the late 15th Century as part of the larger pageant of European history, in which neighboring powers had their own roles to play, and that it might or might not fit neatly into a template of Muslims and Christians fighting each other. But it seems that the rules are organized in a way that makes the game harder to learn than ought to be the case, so that they tend to obscure the designer’s good ideas rather than illuminate them.

I’ll admit, I have not read the rules. But my companions had, and they kept referring back to them as we played. So I draw on their comments, which were copious and not a little irritated at the number of exceptions and special rules that kept them double-checking the rules to make sure they were remembering correctly. “Wait — isn’t there a special rule for fortresses in Granada? Let me check that….” Or, “I think it’s different for the French, isn’t it?” This seems to make learning the game a slog, all the more so because it’s grafted onto a rules system that is meant to be, at worst, moderately complex.

It’s not hard to describe the cognitive flow of how we learn game rules. We read a statement of general principle that tells us how a certain aspect of the game works — using the numbered organization scheme developed by SPI in the 1970’s, you would see something like “Section 3.0: Movement” and you would read a broad-brush description of how to move units. After that, we learn in greater detail through sub-headings (numbered 3.1., 3.2, etc.), but everything still flows from and connects to what we learned in the statement of general principle. If exceptions to the rules need to be stated, they exist at yet a lower tier of organization (section 3.1.1, 3.2.1, etc.). Some exceptions and special rules are not hard to absorb, but the problem is that each one by their very nature cuts against the grain of what you just learned, so they make it more laborious to comprehend the whole of a game. My own opinion as a player and a designer is that you should avoid them to the extent possible for that very reason.

It seems that Diaz Narvaez has taken some flak since Tanto Monta was published for throwing too many finicky little rules into the pot. To be fair, though, over time my companions and I decided that much of the problem with learning the game could come down to how the rules are organized and presented, not just their quantity. It may be that his mistake was trying to force everything into a pyramidal, top-down structure rather than separate all of the universal rules from the exceptions and special rules and present them separately by the faction to which they apply, as Ed Beech did in Here I Stand. In fact, Beech himself said that the best way to learn Here I Stand is to read the general rules, then focus only on the faction that you will play; learn their special rules and ignore everyone else’s until you feel comfortable with the system. Since Beech developed Tanto Monta, I’m a little surprised that he didn’t enforce that approach here as well.

In the end, though, it’s hard to shake the feeling that there are just too many picky little rules in Tanto Monte than there ought to be, making it slower to learn and more of a grind to play than should be the case. My feeling about special rules and rules exceptions pretty much echoes the advice that the celebrated editor Maxwell Perkins once gave John Dos Passos, to go back through what he’d written and eliminate every single adverb. Of course, it’s impossible to write (let’s say) a novel without once modifying a verb, nor is it desirable. But if you focus on not over-using them, that makes your writing leaner, more efficient and more forceful. Same with picky little game rules. As to why designers fall into this trap, I have some ideas about that. They will have to wait for another post.

Sounds like trying to staple on some historical accuracy to a set of more streamlined rules.