I could introduce this post by noting that the body of legends and literature about King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table have fascinated me since I was young. But you might well respond, “And that makes you special… how, exactly?” And you would be right. But it does explain why, at one point, I devoted some time to brainstorming a campaign for King Arthur Pendragon, Greg Stafford’s roleplaying game that has long held pride of place — and understandably so — as the definitive attempt to craft an RPG from the Matter of Arthur. I never ran it (indeed, I never even finished writing it out), but I plan to share my notes with paid subscribers over the next month or so, along with my thoughts on where it might have led.

Before we get to that, I’ll share my thoughts on the game in its final form, King Arthur Pendragon Fifth Edition, and The Great Pendragon Campaign, Stafford’s epic guide to creating a Pendragon campaign. The TLDR version: There’s much in Pendragon 5E and The Great Pendragon Campaign that is clever, erudite and well-thought out, but to a pedant like me, its ambition — which is a big reason why it has earned its claim to be the definitive Arthurian RPG after all these years — is also a source of awkwardness that both books sometimes acknowledge, but also try to elide.

It is clear throughout that Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur is Stafford’s main source of inspiration. He says right out that Pendragon, at its beating heart, is a game about roleplaying as King Arthur’s knights. The language that he uses to describe and express the essence of knighthood reeks of the high medieval period and reminders that French was the not only the language of chivalry, but the native language of so much famous Arthurian literature. This makes sense, as Le Morte d’Arthur represents the culmination of the high medieval — and largely French — version of the Arthurian mythos, which is the version that probably looms largest in the popular imagination.

However, Malory’s vision of Arthur and his world is far from the only one. Writing in the late 15th century, he stood at what was even then one end of almost a thousand years of lore, during which the source material was reimagined and reinvented. It is now widely understood that Arthur first appeared in Welsh folk legends that consoled the Celts of post-Roman Britain who had been pushed to the fringes of their island by decades of Saxon immigration and expansion. In the 12th Century, Geoffrey of Monmouth forged the Matter of Arthur into an English national myth as early Norman England tried to figure itself out. He created Arthur in a form that the Kings of England tried to use to their advantage well into the Tudor period. Remember how Henry VIII “discovered” the Round Table and displayed it at Hampton Court? Later in that century, Chretien de Troyes refigured the Knights of Round Table as heroes of chivalric romance, a genre that flourished for two hundred years after his death, and which Malory tied together with a flourish. Four centuries after Malory, Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote Idylls of the King as a tragedy of the rise and fall of a civilization, complete with a warning to Queen Victoria to make sure her own empire would not come to a bad end. In the mid-20th Century, T. H. White created Arthur in The Sword and the Stone as the young, earnest and somewhat moralistic hero of a children’s story — who defends England from Norman invaders, curiously enough. More recently (and to be fair, the movie post-dates Pendragon 5E), Guy Ritchie refigured Arthur as a sort of admirable gang leader in King Arthur: Legend of the Sword. One critic dismissed it as, “chav King Arthur,” but I found it not quite as outlandish as it sounds.

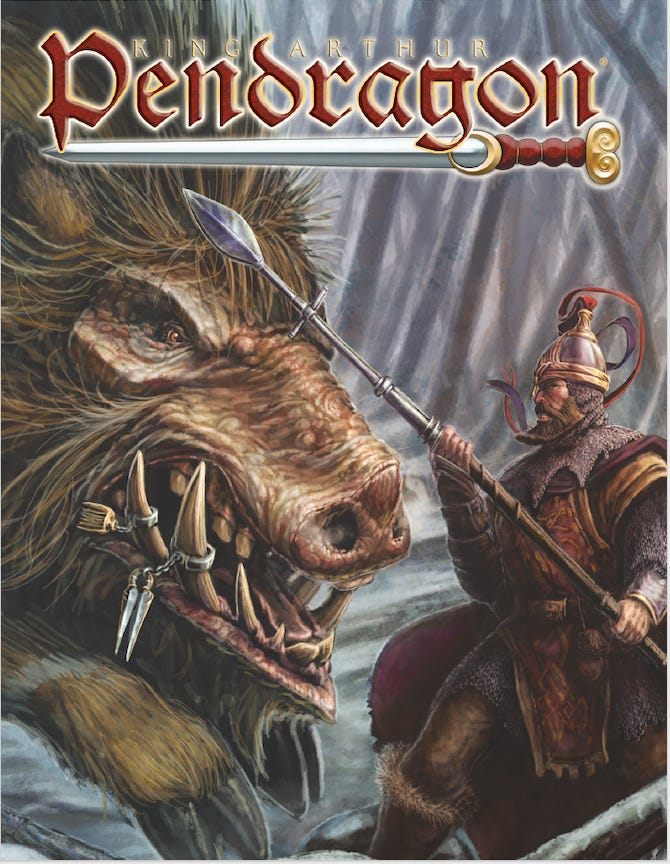

Stafford acknowledges that Arthur has worn different sets of clothes through the centuries, but insists from the very beginning that these guises can fit together in the same wardrobe. The cover art illustrates King Arthur and the Troit Boar, of which he writes:

The original story is a savage and wild tale of the Welsh Arthur, a supernatural chief of superhuman men in a fairy-tale world of wonder and terror. The game herein is set in a world based on later sources, where Arthur and his court are the sophisticated Knights of the Round Table, a court of knights both chivalrous and brutal. Yet it also includes the legends of the more primitive Welsh stories, the more refined French epics, the gentlemanly English poems, and the Grail legends. It is the world of the greatest king in the world, where you participate in the realm of King Arthur Pendragon.

Well, yes… But those Arthurs don’t necessarily fit well together because those more closely you look at them, the more you realize that they were created with different purposes in mind. You can cram all of them together under that tent, but sooner or later they’re going to start arguing over who is the real King Arthur.

But I’ll admit it once again: This is just pedantry on my part. Probably, I harp on it because, even though I read through both the Pendragon 5E core rules and the Great Pendragon Campaign, I never actually ran or played the game. With that in mind, I will say that if you are willing elide these discrepancies and embrace the game that Stafford wrote, it’s worth giving it a spin. In particular, three aspects of the system and the setting impressed me.

Without having tried it out in practice, I will say that the Traits and Passions system seems to capture an important essence of the setting without railroading the player characters. At the center of the high-medieval Arthurian romances sit the personalities of individual knights. The trick in bringing to life a roleplaying game based on them, then, is to get the player characters to act according to the world in which they live without depriving players of choice or the characters the possibility of acting out of character. When you create your character, you assign numerical ratings to Traits and Passions. Traits are divided into opposed pairs, such as Prudent/Reckless and Chaste/Lustful, and the scores you assign to each half of that pair must add up to 20. PCs begin with a score of 15 in four basic Passions — Loyalty to Lord, Love of Family, Hospitality, Honor — and a score of 3d6 in Hate of the Saxons. At key moments, the GM may require you to make a Trait roll to influence what your character does. Passions enter play at the player’s discretion; you may choose to roll against one of your Passions to gain a bonus to a skill roll, but failure can have persistent negative consequences for your character’s state of mind (c.f., the madness of Lancelot).

Similarly, the use of opposed rolls in the combat system is both clever and true to the source material. Yes, combat is more cumbersome when both attacker and target have to roll dice to resolve an attack than having the attacker roll against a passive target number. But it gives the defender a sense of agency, and it also focuses your attention on the individual whom your character is attacking. It makes perfect sense as a way of simulating single combat, and let us not forget that single combat against another knight is going to be the ultimate test of your character’s mettle in this setting.

I will also give Stafford a nod for skillfully handling what is probably the most vexed issue in the setting for a contemporary RPG audience — the limited roles open to women in high medieval society, which would seem to inhibit what you can do with female player characters. Whether or not you want to argue that men and women are highly unequal in this setting, it is true that they are separate. Canonically, there are no female Knights of the Round Table. However, Stafford goes on to elaborate plausible ways of working around this barrier, starting with the fact that there are actually a fair number of important female characters in the Arthurian mythos, from Morgan le Fay to the various sorceresses in Malory to the paramours in the chivalric romances who exert real influence on the knights who fixate on them. As he puts it, “Because women are effectively blocked from great personal achievement, they often find their outlet for power and respect by manipulating and controlling men. Some men do not mind this.”

Stafford also notes that, looking at medieval history, you can find high-status women who exerted real power and influence in their own right (the redoubtable Eleanor of Aquitaine being perhaps my own favorite example). And that mining legend and lore produces examples of fictional women who flourished in conventionally male roles — like the Amazon queen Hippolyta — who can model for female player characters. They may be rare, but it’s not like RPG players can’t stand characters who play against type. Finally, he notes the time-honored device of female characters who disguise themselves as men. Tolkien used it to powerful effect, but you can also trace it back to Shakespeare, in whose plays the boy actors who played women sometimes had to play women pretending to be men. In other words, Stafford concedes, “Yeah, this is something you can’t really do and stay true to the setting…” and then he proceeds to explain, at length, various ways that you can get around it. Impressive.

The Great Pendragon Campaign is a bulkier tome than the 5E core rule book and it functions more or less as the game master’s guide to King Arthur Pendragon. You probably don’t need it if you just want to play a character, but it is exceedingly useful if you intend to run a game. It contains a creature appendix, rules for resolving sieges, character aging and advancement, aspects of realm management, an explanation of The Wastelands and how that whole business fits in with everything else, and it ends with an adventure module called “The Goblin Market,” based on Christina Rossetti’s poem of the same name. It’s a nice nod to the influence of Arthuriana on the Pre-Raphaelites and the Victorians in general.

The bulk and heart of the book, though, is a year-by-year chronicle of Arthur’s life, starting with his birth in 485 AD and ending with his passing in 566. It’s useful in that it places the key events from the various versions of the legend into temporal relation to each other and to the phases of Arthur’s life, and Stafford scatters it with adventure seeds based on the canonical events in it.

The weird thing about it, though, is that, like Pendragon RPG as whole, it mashes together history with various strands of legend and they don’t always fit smoothly together. It’s like reading an argument that goes off in several different directions at once. Did you know that post-Roman Britain was troubled by Irish pirates and Pictish marauders as well as Saxon incursions? You will after reading through The Great Pendragon Campaign. Good to know, but how smoothly does it fit in with The Waste Land, the Holy Grail, or the war between Lancelot and Gawain’s clan that ultimately broke Camelot? All of those are canonical, but they come from different parts of the canon that were invented with different purposes in mind. They’re all interesting; they’re all worthwhile. But when you mash them all together, the borders between them never quite disappear and it can be hard to experience all of them as part of the same whole.

Or maybe it’s not hard at all. Ultimately, my judgment of King Arthur Pendragon 5E is that you can’t beat it as an expression of the high medieval version of the legend, but trying to ground it in history and other versions seems kind of jarring to nerds like me. But you can enjoy it even if you are a nerd like me, and if you’re not you can disregard my pettifogging and just get on with having fun. Next: The paying customers get a series of looks at how I tried to fit my own obsessions with the Matter of Arthur into the game.

[If you’re not a paid subscriber, you can become one gain access to rest of my musings on King Arthur and the Pendragon RPG by using the subscription link that Substack will insert somewhere in this post. Or you can take advantage of this special introductory offer: Kick in $5 through the PayPal or Buy Me a Coffee links below, and I’ll manually add you as a paid subscriber for 2 months.]

Sounds like you ought not run Arthur's entire life then.

On the relationship between the layers of history and myth, while I’m usually not a fan of ripping stories from their cultural historical context and transposing them somewhere else, I find that I don’t mind this in the context of ‘Pendragon’. This is probably related to the fact that I know a lot more about late medieval England than I do about post-Roman Britain and so the employment of a lot of Malory’s material suits my personal knowledge base and subjective preferences. I still find ‘Excalibur’ with its pastiche of 15th century culture and aesthetics a more engaging interpretation of the stories on film than those that adhere more closely to ‘the history’.

I’m conflicted about mechanics that compel negative consequences on characters. On the one hand, I dislike mechanics that seek to compel me to do things that I should want to do in a game without that compulsion. If I’m playing in a world of ‘courtly love’ then I should want my character to explore the tension between duty and honour, loyalty and love. Any mechanic that tries to force the issue will inevitably be more limiting than simply engaging with those themes and consequences as they emerge through the narrative of the game. And if I don’t want to explore those things, then making it a mechanical necessity just sets up a tension between system and play style. I feel the same about the ‘hunger’ mechanic In ‘Vampire’. If I’m playing VtM as a game of personal horror, then I don’t need a mechanic that compels my character to face the nightmare of what it means to be an immortal predator. But if I’m playing it as a game of ‘supermen in flouncy shirts’ then I’m going to resent or ignore that mechanic anyway. On the other hand, I accept that my preference for playing flawed characters and then torturing them with a series of intractable trolley problems is, perhaps, a rarified taste and game designers who want to inculcate a certain tone that is, perhaps, at odds with ‘heroic’ RPG culture must sometimes mechanise it to achieve their goals.